Steering into the Future: Uber and Lyft

Will Robotaxis Leave Uber and Lyft in the Rearview?

Riding on Autopilot

Imagine tapping your phone for a ride, and an empty car rolls up. No driver waves hello; just you and a talking dashboard.

Uber and Lyft redefined how we hail rides, but a new challenger is revving up: autonomous vehicles. The question now is whether ride-hailing giants will smoothly embrace this driverless tech or get stuck in the slow lane.

It’s a fun scenario to picture unless you’re an Uber or Lyft executive wondering if your business model is about to be disrupted.

Let’s buckle up and explore how self-driving upstarts like Waymo, Cruise, Tesla, and more are threatening to upend the rideshare world, and what it all means for the business of getting from Point A to Point B and for YOU as a passenger/investor.

Uber & Lyft Today – On Top, But Checking the Rearview

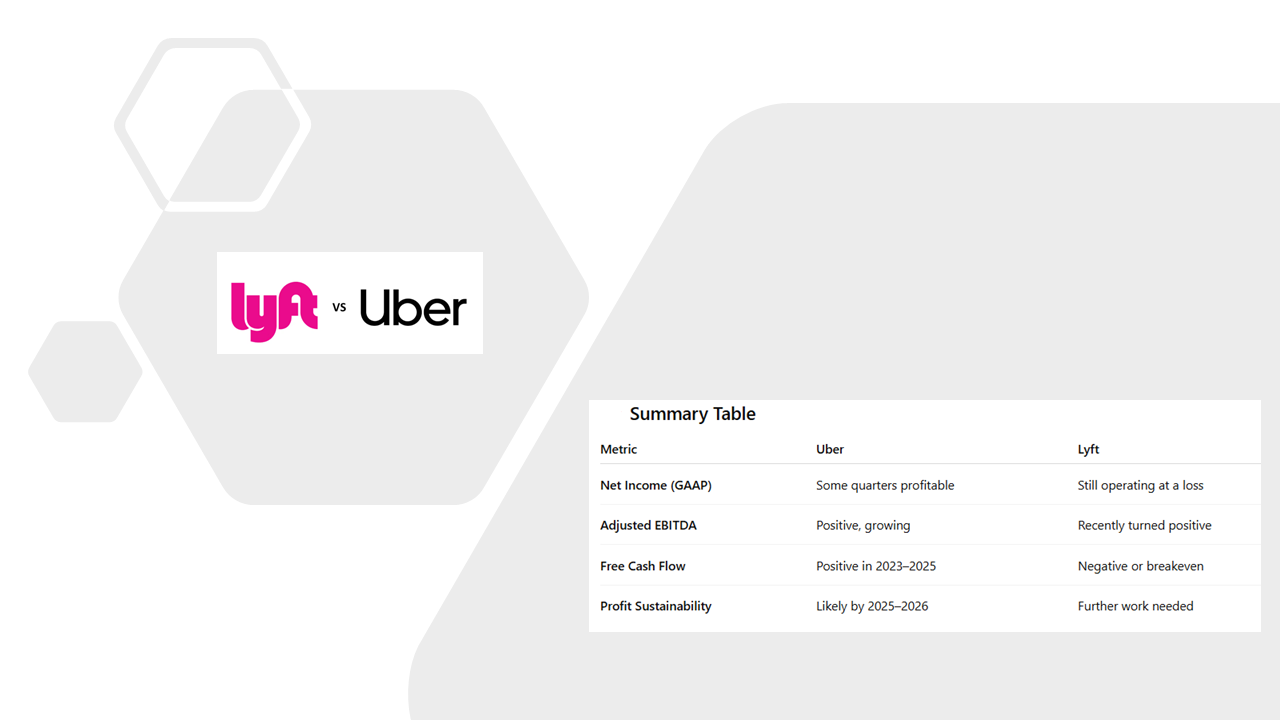

Uber and Lyft dominate ride-hailing, facilitating millions of trips and generating hefty revenues, yet profits remain elusive, and the road ahead is uncertain.

Both companies once poured money into developing self-driving tech in-house, only to hit speed bumps. Uber’s costly autonomous division suffered a high-profile fatal crash in 2018, prompting the company to sell its self-driving unit to the startup Aurora in 2020.

Uber took a stake in Aurora as part of that deal, effectively outsourcing its driverless ambitions while keeping a foot in the game.

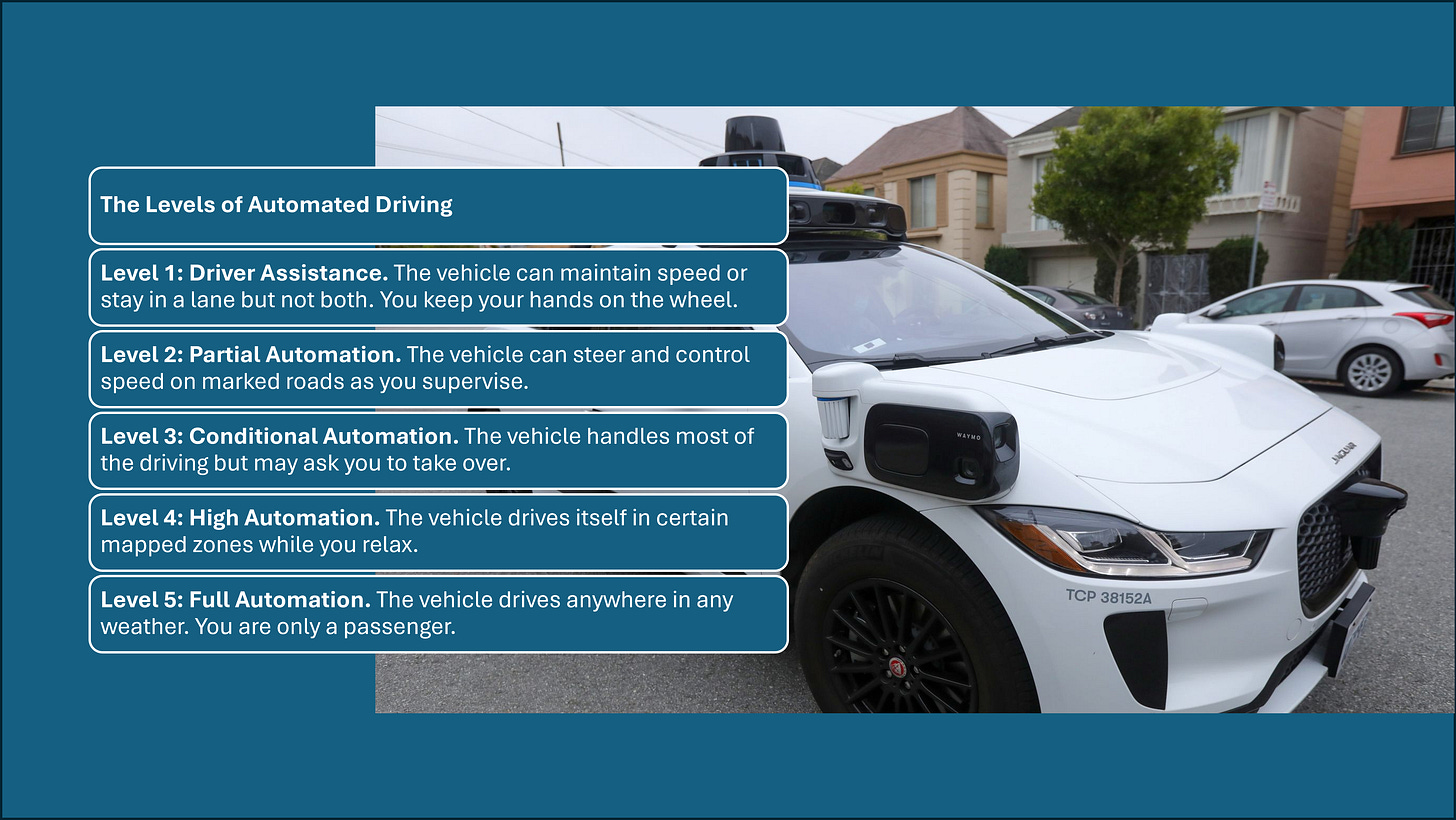

Lyft made a similar U-turn, selling its “Level 5” (I’ll explain later what this is) self-driving division to Toyota’s Woven Planet for $550 million in 2021 to cut losses and reach profitability faster.

Having shed the expense of building autonomous tech from scratch, Uber and Lyft shifted gears to partnership strategies. Today, both companies still rely on armies of human drivers for virtually all rides.

But they’re also busy lining up alliances with the autonomous vehicle (AV) upstarts that aim to replace those drivers. In other words, the rideshare leaders are hedging their bets: enjoying the current dominance of their platform while preparing for a future when your Uber or Lyft might have no one behind the wheel.

It’s a delicate balance as they must keep drivers (and regulators) happy now, yet embrace the driverless revolution that could make those drivers obsolete tomorrow.

Waymo & Cruise – The Autonomous Assault

Waymo, Google’s well-funded spin-off, is leading the charge in robotaxis. Waymo’s self-driving cars are ferrying customers with no human operator and racking up serious numbers in Phoenix, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Austin.

There have been some concerns by passengers over: (1) Technical Glitches, (2) Drop-off Challenges, and (3) Service Limitations.

In fact, Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai recently revealed that Waymo is now completing over 250,000 paid rides per week in the U.S.. Waymo’s rider-only “Waymo One” service is no longer a science experiment; it’s a burgeoning business that’s starting to dent the universe of urban transport.

Backed by GM prior and wholly owned as of February 2025, Cruise had been neck-and-neck with Waymo, operating driverless ride-hailing in San Francisco and testing in Phoenix and Austin. Their fleet of distinctive Chevy Bolt robotaxis hit a milestone of over 700,000 driverless trips in California in 2023 before plans skidded off course.

A series of mishaps (including a much-publicized incident where a Cruise car dragged a pedestrian on a city street) prompted California regulators to suspend Cruise’s permits in late 2023.

By early 2024, Cruise had “paused” all driverless operations amid safety investigations, and reports emerged that parent GM was restructuring or even shuttering major parts of the unit after investing $10 billion.

This abrupt pit stop for Cruise has left Waymo as the undisputed front-runner in U.S. robotaxis for now. It’s a vivid reminder that the autonomous road is bumpy; technical prowess alone isn’t enough without public trust and regulatory green lights.

Not to be forgotten are other players revving their engines in the autonomous arena. Motional, a Hyundai–Aptiv joint venture, is testing robotaxis in Las Vegas (in partnership with both Uber and Lyft) under a 10-year deployment deal.

Zoox, owned by Amazon, has developed a spaceship-looking driverless shuttle and is running pilot rides around San Francisco’s Treasure Island as it eyes commercial service.

Startup May Mobility is launching autonomous shuttles in 2025 (teaming up with Uber in Arlington, TX). Even Chinese AV firms like Baidu’s Apollo Go, AutoX, and Pony.ai are making strides abroad.

In short, Waymo isn’t alone; a crowd of tech and auto companies is competing to bring robotaxis to the masses. Each of these could become a formidable competitor or a potential partner to Uber and Lyft.

The key question is: will the ride-hailing giants be disrupted by an upstart’s superior technology, or can they harness these new technologies to reinforce their own platforms?

Tesla’s Wild Card – The Elusive Robotaxi Fleet

No conversation about autonomous disruption is complete without Elon Musk and Tesla, who have been loudly promising a self-driving revolution from a different angle.

Unlike Waymo and Cruise with their dedicated taxi fleets, Tesla’s strategy is to leverage the millions of Tesla cars already on the roads via over-the-air software updates.

Musk has long teased a vision of a “Tesla Network” where Tesla owners could let their cars operate as robotaxis to earn extra income when they’re not using them. It sounds like a nightmare for Uber/Lyft (millions of privately-owned autonomous taxis swarming the streets, effectively crowdsourcing a competitor network) except for one sticking point: true full self-driving capability isn’t ready yet.

Tesla’s current Full Self-Driving (FSD) software is advanced driver assistance, but still Level 2 (requiring an attentive human as shown below); impressive, yet not the hands-off robotaxi Musk keeps predicting.

That hasn’t stopped Musk from making bold timelines. In late 2024, he unveiled a prototype “Cybercab” (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office refused to grant the company trademarks on "Robotaxi" as well as "Cybercab”) and claimed Tesla would launch unsupervised robotaxi services in cities like Austin by mid-2025, with a dedicated $25,000 steering-wheel-free robotaxi vehicle entering production by 2026.

Musk even took a jab at Waymo, criticizing it for using expensive, custom LiDAR-equipped cars produced in low volumes, whereas Tesla is betting on affordable cars with vision-only tech.

For Uber and Lyft, Tesla represents a tricky threat. On one hand, many Uber/Lyft drivers already use Tesla’s, taking advantage of the lower fuel (electric) costs. But if Tesla flips the switch to full autonomy, those drivers might be out of the equation.

Tesla could activate an Uber-like service overnight using its existing customer app or a new platform, diverting riders to its own network. It would pit Tesla’s brand and massive fleet of owners directly against incumbent ride-hailing platforms.

However, that scenario hinges on technical and regulatory breakthroughs that have yet to fully materialize. For now, Tesla is a wild card: it boasts immense scale and ambition, but Uber and Lyft know all too well that promises of self-driving glory can be far easier made than kept.

Show Me the Money – Economics of Driverless vs. Driver

For all the futuristic cool factor of autonomous taxis, the real disruption boils down to cold, hard economics. Can a ride without a human driver be significantly cheaper (or more profitable) than one with a driver?

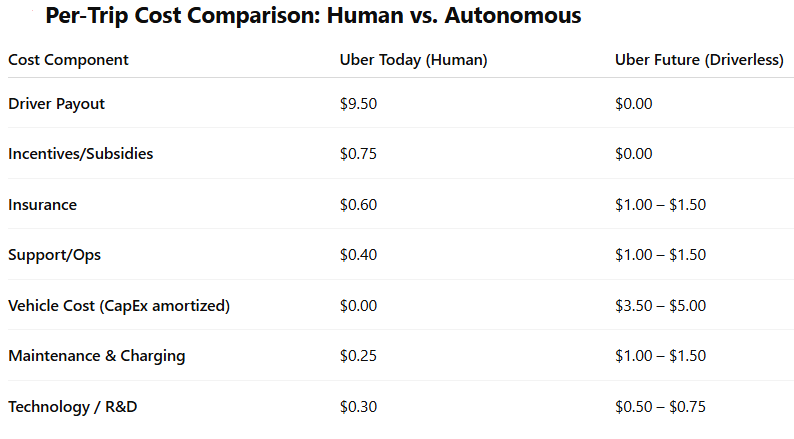

The early signs suggest yes. Uber and Lyft’s biggest cost is paying drivers; roughly 80–85% of each fare goes to the driver in earnings, meaning Uber/Lyft only keep a small slice of the pie. (Even after adding various fees that boost their cut to an effective ~30-40%, the majority of revenue is still consumed by driver labor.)

A robotaxi keeps nearly 100% of the fare for the operator, aside from operating costs. And those operating costs, maintenance, charging, cleaning, and software, could be far lower per mile than a human-driven car when optimized at scale.

What costs are not being considered in the above statement, which no one discusses? Assuming an electric car: electricity, insurance, repairs, and registration fees, which is ~$2,100 – $3,400 annually per vehicle (go with the higher number as insurance for driverless cars is more expensive). This does not include the required infrastructure, as one still needs a human to plug in a car, a secure parking area overnight, etc. Also, now one has to plan for staging and route planning.

The table below provides a rough comparison between driver and driverless operational models. However, the numbers on the right only work at scale, and today in the U.S., there are ~1 million drivers in the Uber/Lyft system.

Waymo has hinted at the magnitude of this advantage. Thanks to Google’s deep pockets and tech, Waymo has spent over a decade refining its self-driving system and sensor suite.

The result: Waymo’s cost to operate a robotaxi is around $0.30 per mile, less than half of Uber’s estimated ~$0.70 per mile cost with a driver. This allows Waymo to price fares about 6–12% lower than Uber on average and still come out ahead on margins.

In Phoenix, for instance, riders report Waymo’s autonomous rides often undercut Uber’s prices for the same trip, especially at busy times when Uber’s surge pricing kicks in.

Unlike human drivers, who need breaks, salaries, or surge incentives, a fleet of robots can work nearly 24/7. In Austin, a limited pilot found that 100 Waymo vehicles were busier than 99% of human Uber drivers in terms of trips per vehicle. A hint of how efficient a well-deployed AV fleet could be.

That said, my take is that if given the choice, one will select driverless out of curiosity, thus the efficiency numbers may be inflated.

However, the economics aren’t one-sided. Developing and deploying autonomous vehicles is enormously capital-intensive. Waymo has reportedly invested over $11 billion into its technology so far.

Each sensor-packed vehicle initially costs hundreds of thousands of dollars to produce, though that is dropping with new models (Waymo’s next-gen robotaxi built on a Geely platform could cost under $30,000 each as sensor costs plummet with scale).

There are also operational expenses that Uber/Lyft don’t directly bear today: owning and maintaining a fleet (currently, drivers supply and upkeep their own cars in the Uber/Lyft model). Empty miles – time when a driverless car repositions with no passenger – still incur costs.

And early robotaxi services have needed lots of on-call support, from remote technicians to teams ready to physically rescue vehicles stuck in unusual situations (say, confused by a construction zone or a row of traffic cones).

In short, while autonomy promises a radically lower cost per ride in the long run, it comes with high up-front investments and new kinds of overhead.

Uber and Lyft have enjoyed an “asset-light” model (no vehicle ownership, minimal capital expenditure) and switching to an autonomous fleet world could upend that, compressing margins for whoever runs the fleet.

The big bet, of course, is that eliminating driver pay more than offsets these costs. If that bet pays off, the first company to scale up robotaxis widely could potentially underprice all competitors and capture a huge market share.

That looming economic reality is what keeps Uber and Lyft’s leadership up at night and has them scrambling to make sure if driverless rides take off, they’re not left without a seat (or rather, a vehicle) in the game.

Roadblocks – Regulatory, Geographic, and Human Hurdles

Even if the technology and economics fall into place, the fate of autonomous ride-hailing will also depend on regulators and plain geography. As of 2025, the legal and public acceptance landscape for robotaxis is a patchwork.

In San Francisco and Phoenix, regulators have allowed full commercial driverless ride services, albeit with some stumbles. San Francisco’s officials, for example, initially green-lit Waymo and Cruise to operate 24/7, only to witness a series of odd mishaps; stalled AVs blocking traffic, confusion around emergency scenes, and that infamous Cruise accident.

The blowback led California to tighten the leash on Cruise and subject Waymo to greater scrutiny. In New York City, by contrast, the attitude is far more cautious. In 2024, NYC’s mayor announced that no fully driverless cars will be allowed for now.

Companies can test AVs in NYC only if a safety driver is sitting at the wheel. Officials made it clear that Manhattan’s chaotic streets won’t see empty robotaxis anytime soon, essentially declaring that “this technology is coming whether we like it or not, so we’re going to make sure we get it right”.

Regulatory hurdles also vary by state and country. Arizona embraced AV testing early (hence Waymo’s heavy Phoenix presence), while California’s approvals remain trial-based and revocable at any moment safety issues arise.

Some states have outright prohibitions on autonomous vehicles or require special permits that slow deployment. Overseas, rules differ wildly; Europe has stringent safety regulations that have kept most robotaxi trials in pilot mode, and places like London or Tokyo have yet to see any major self-driving ride services due to legal barriers.

Geography and climate pose another challenge: the current generation of AVs struggles in heavy rain, snow, or fog. That’s one reason most deployments have been in sunny states like Arizona, Texas, or temperate urban cores of California. Scaling to Chicago blizzards or torrential monsoons will take further technological hardening (and likely regulatory proof).

Then there’s the human factor. Driverless cars sharing streets with human drivers and pedestrians is complex. Every incident no matter how small can become big news and shape public perception.

Some riders absolutely love the novelty and safety promise of robotaxis; others are nervous about the idea of no driver in control. Ride-hail drivers, understandably, worry about their livelihoods. Labor groups in some cities are already lobbying for limits on robotaxis or provisions to retrain drivers for other jobs if automation reduces driver demand.

Uber and Lyft also face a PR balancing act: they need to champion innovation but risk alienating the very drivers who currently power their platforms. We’ve seen hints of tension, like drivers protesting when Uber experimented with AVs in their city, or demanding that companies commit to not replace them outright.

Regulatory bodies, often influenced by public sentiment and lobbying, will be weighing safety data, economic impact, and constituent fears as they decide how fast to open the gates for autonomous vehicles. In summary, the path for robotaxis is as much about navigating city hall and societal trust as it is about algorithms and sensors.

Takeaways for Business Leaders

Disruption Isn’t Binary: The rise of autonomous vehicles doesn’t automatically spell doom for Uber and Lyft; adaptation is possible. The likely scenario is a gradual hybrid model where old and new co-exist. Businesses facing disruptive tech should seek ways to integrate or partner with the disruptors, rather than assuming an all-or-nothing outcome.

Partnerships as a Strategic Pivot: Uber and Lyft’s response; teaming up with former competitors like Waymo, or enabling third-party AV fleets on their apps – highlights a key strategic lesson: when a core technology is out of reach, ally with those who have it. This can turn a threat into a mutual opportunity (at least in the transitional period).

Cost Economics Win in the End: Whether or not Uber and Lyft remain on top may ultimately come down to unit economics. Autonomous tech promises a dramatic cost reduction per mile. Businesses must rigorously monitor cost trends; if a competitor finds a significantly cheaper way to deliver the service (be it through automation or other efficiency), it will upend market dynamics. Uber and Lyft are racing to ensure they share in the cost advantage of driverless fleets rather than being undercut by it.

Regulation and Public Sentiment Matter: The case of Cruise’s abrupt halt shows how regulatory risks can derail even the best technology. Leaders in any industry should engage proactively with policymakers and address public concerns early. Winning hearts and minds (ensuring safety, communicating benefits, being ready to self-regulate) can be as important as winning the tech race.

Continuous Innovation vs. Core Focus: There’s a balance to strike between exploring moonshot innovations and doubling down on core competencies. Uber and Lyft shed their moonshot projects to fix core operations and profitability, then re-engaged with innovation via external partnerships. Business leaders should evaluate when to build in-house, when to partner, and when to step back and let others take the R&D risk; all while keeping a long-term vision.

Closing – The Road Ahead

Uber and Lyft find themselves at a crossroads not unlike the one traditional taxi companies faced a decade ago. They once were the insurgents; now they must avoid becoming the disrupted.

The race between ridesharing giants and autonomous vehicle upstarts is on, and it’s not just about who gets there first; it’s about who finds the right model to thrive when they all arrive.

Will the next five years see Uber and Lyft successfully operating mixed fleets of human and robot drivers, or will names like Waymo and Tesla become the new default for catching a ride?

The road ahead is full of twists and turns, but one thing is certain: the concept of “going for a drive” will never be the same. As we watch this journey unfold, every business leader should be asking themselves a forward-looking question: In a world where cars can drive themselves, what value can we add, and how do we ensure we’re not left behind when the future comes rolling in?

Sources

Insights and data in this newsletter are drawn from publications and research, including:

Henry Chandonnet, “Uber is hedging its bets when it comes to robotaxis,” Fast Company, May 10, 2025.

Jarry Wu, “Waymo Than Meets the Eye,” Ivey Business Review, Dec 31, 2023.

“Lyft Announces New Round of Autonomous Partnerships,” Lyft Press Release, Nov 6, 2024.

Tina Bellon & Eimi Yamamitsu, “Toyota to buy Lyft unit in boost to self-driving plans,” Reuters, Apr 26, 2021.

Kirsten Korosec, “Uber sells self-driving unit Uber ATG in deal with Aurora,” TechCrunch, Dec 7, 2020.

Andrew J. Hawkins, “New York City welcomes robotaxis — but only with safety drivers,” The Verge, Mar 28, 2024.

Chris Kirkham, “Tesla’s robotaxi event long on promises, short on details,” Reuters, Oct 11, 2024.

Aarav Shen, “Waymo Surpasses 250,000 Weekly Robotaxi Rides as It Expands in the U.S.,” Beijing Times, Apr 25, 2025.

Great topic. I became acquainted with it reading the 2019 book Rule of the Robots which goes into this situation in great detail. It’s shocking that in SF in its first year, Waymo has already captured around 20% of the market. My looming questions are, how many people will have to be out of a job before universal basic income becomes a serious discussion point? And secondly, with our future becoming oh so dystopian, will that genre have to be renamed to reality lit?